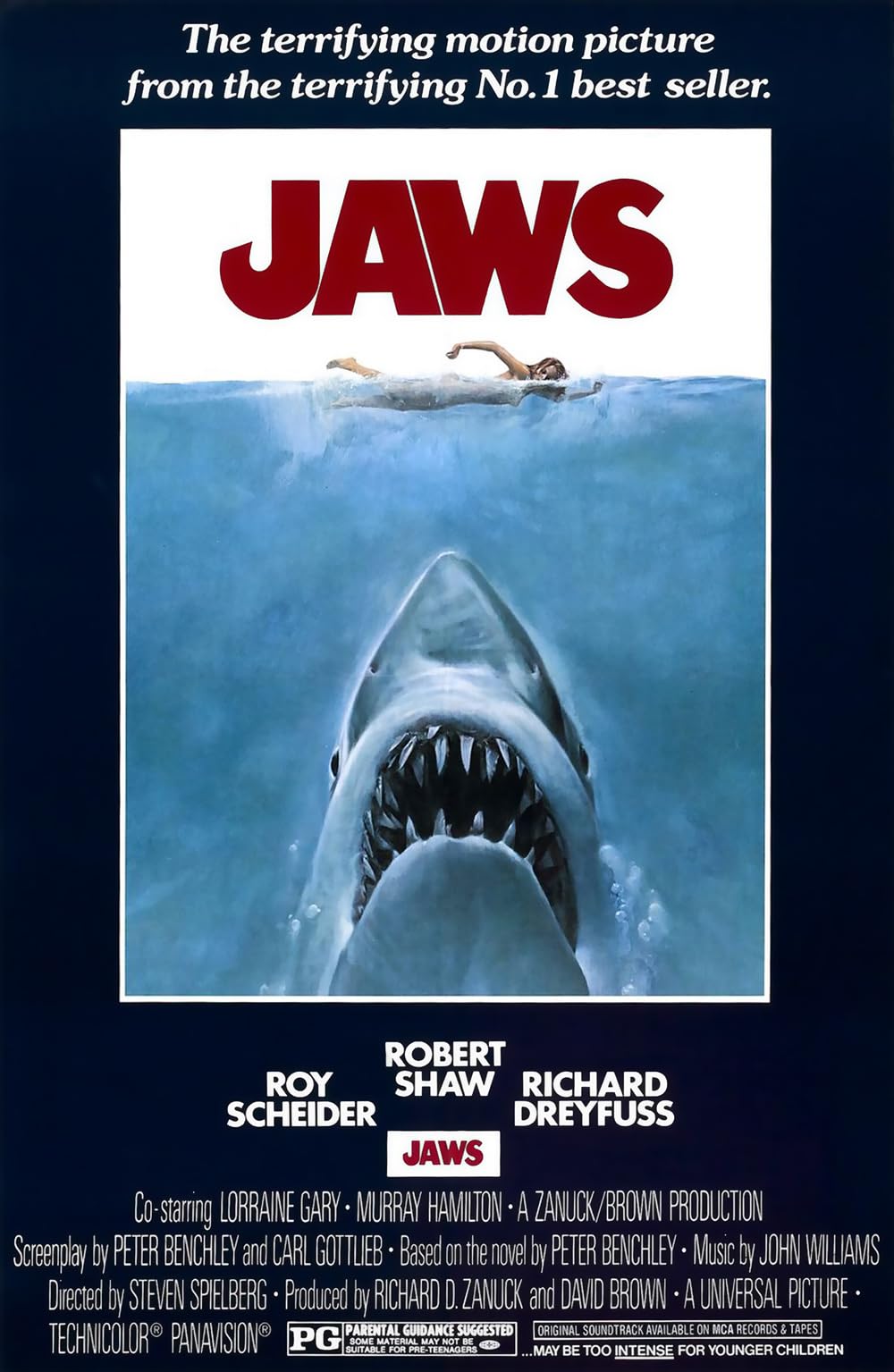

Jaws

124 min

Dir. Steven Spielberg 1975

Hidden among Steven Spielberg’s decades long schmaltz vending career are a few good movies. While his technical skills are always evident, as a storyteller Spielberg peaked with a couple of high concept creature features: Jaws and his two Jurassic Park movies. Both of the films spawned entire subgenres of copycats and knockoffs trying to tap into both the narrative and cultural success of the originals as well as launching successful film franchises. Jurassic Park was preceded by several ‘prehistoric monster’ films like King Kong (1933) and dinosaur movies like The Land Before Time (1988, with Spielberg as a producer), but Jaws very nearly launches the concept for the shark attack movie. Prior to Jaws, if sharks appeared in film, it was mostly as background hazards in adventure genre films with a few cameos elsewhere like in the James Bond film Thunderball (1965). And while none of the Jurassic Park derivatives outside the parent franchise have been particularly acclaimed nor commercially successful, Jaws inspired a whole slew of commercially successful films like Deep Blue Sea and The Meg as well as a few well reviewed movies like The Shallows. Jaws was and remains a cultural phenomenon. So what’s it all about?

In Peter Benchley’s novel, Jaws takes place off Long Island but in the film it’s Amity Island, a fictionalized version of Nantucket. The story opens with a drunk kid getting eaten by a shark. Chief Brody (Roy Sheider) searches for the girl and finds her remains. The medical examiner initially finds the girl died of shark bite which sets up the narrative fulcrum upon which the rest of the story, and most of the genre, operates.

Eager to stop news of a shark attack from hindering summer tourist business on the island, Mayor Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) convinces the medical examiner and then Chief Brody to declare that the girl was mangled by a boat propeller while swimming, not a shark. Without this decision, common to all levels of government in capitalist states, to protect capital accumulation instead of the population, the story cannot move forward because the beaches would be closed and there would be no further human infested waters where the shark could dine. But greed wins out, the beaches remain open and the bodies pile up, what’s left of them anway. This is a central point of the genre which usually finds either human greed or hubris – usually scientific – to be the basis that allows for killer shark stories in the first place.

After the death toll becomes politically untenable, a marine biologist (Richard Dreyfuss) convinces everyone it is a shark and the beaches have to close anyway, Mayor Vaughn approves the hire of a professional fisherman, Quint (Robert Shaw) to hunt down the fish. Quint’s subplot is more or less a Moby Dick Cliff Notes, especially his ending! Quint’s dockhouse is filled with mounted shark jaws of various sizes and his hunt becomes framed as personal revenge against the sharks that ate his boatmates after a Japanese submarine torpedoed the USS Indianapolis in World War II. His narrative arc is definitely Ahab’s. Quint and the biologist Hooper invoke Moby Dick again in their comparison of their prior injuries and scars from shark encounters. Quint, Hooper and Brody then quest to hunt down the great white shark that is munching on tourists and locals.

The film becomes increasingly silly as the three leave behind the political economic intrigue that allowed for the shark attacks in the first place. By the incredibly low standards of shark attack movies, Jaws appears practically peer reviewed from a science perspective. It still requires a series of nonsensical decisions and pseudoscientific shark biology in order for the Man vs. Shark portion of the film to build suspense or seem plausible. The shark hunters have harpoons, explosives, fish hooks, pistols, shotguns and more. Any hostile interaction with the shark where the people are not submerged in the water can only plausibly end in one way. In short: people go fishing, fish do not go peopling.

Jaws is very nearly the only shark attack movie, and one of very few animal attack movies of any kind, where the Horror Animal does not eat impossible amounts of food. That the shark continually preys upon people is implausible but since it’s not clear over how many days the narrative takes place, the volume of soylent green (plus one black labrador) the shark eats only moderately stretches plausibility. Some shark attack movies have the shark eating over a year’s worth of food over the course of a day or two. Jaws is positively restrained in having the shark eat only a couple months of food over a week or two. Yet this exaggeration is still part of creating a monster where, in reality, there is only a shark. It’s a puzzle. The film already has capitalism as the monster, as the problem that allowed for all but the first person to be eaten by the shark. Why does it need a second monster? Why can’t the shark just be a shark? Is an animal that does, on very rare occasions, kill and eat people so insufficiently terrifying that it must be exaggerated? And how does killing the shark solve the political problem that put people in harm’s way?

Jaws succeeds as a film for a lot of different reasons. Spielberg does his career best pacing and speeds up and slows down the film at several moments without rushing or dragging. The special effects would mostly pass muster today, unlike its sequels. And most of all, terrific performances from the four lead characters. Sheider, Shaw, Dreyfuss and Hamilton are all stellar with Shaw especially good in bringing to life what could have been an empty archetype. Hamilton as a politician only interested in the tourist economy is wonderful. You can feel the hollow salesmanship when he says, “Amity, as you know, means friendship,” while trying to distract a news crew from the shark attacks they’ve come to cover.

Jaws basically invented the nature horror subgenre of the shark attack movie and remains one of its best examples even after nearly fifty years and dozens of imitators. It is also a film that repopularized sharks as villains and probably plays some role in mass shark slaughters though commercial fishing was already doing that before Spielberg was born because, just as in the film, capitalism is the real monster, the one that magnifies all harm.