This essay is greatly informed by analytical and ethical frameworks developed by Christina Sharpe, Frank Wilderson, Saidiya Hartman, Fred Moten, Che Gossett and others along with Marcus Rediker’s historical research even where not directly cited though they cannot be blamed for my failings. Specifically I use Rediker’s historical scaffolding in his essay “History below the water line” which I abuse to talk about shark attack movies. Should you find this essay engaging please uplift their works, the directly influential ones being listed at the bottom. Special thanks to Megan Spencer for their valuable feedback on the draft and to both Megan again and Zoé Samudzi for being thought partners on the ideas while writing. I try to avoid detailing anti-black violence yet found no way to escape implying or vaguely describing some easily imaginable and horrible scenarios so a HUGE CONTENT WARNING FOR ANTI-BLACK VIOLENCE AND AFRICAN SLAVERY is in order. Feedback whether constructive, destructive or other always welcomed.

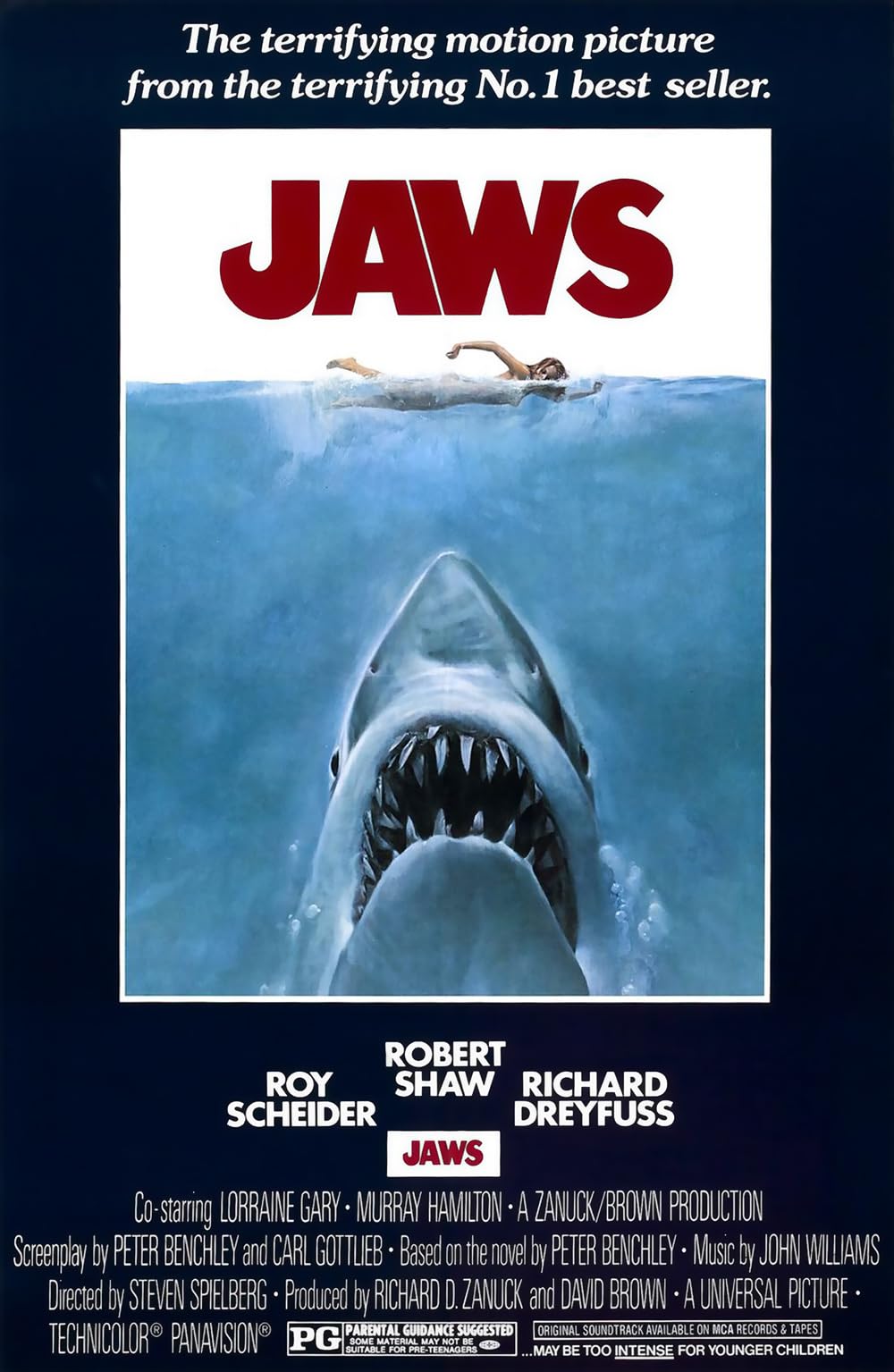

The 2018 box office hit The Meg proved that the shark attack film remains a staple of the nature horror genre. The Meg has already a sequel in development and spawned a knockoff in the same year, Megalodon. These focus on groups of people under threat from one or many otodus megalodon sharks, a species extinct for over two million years that grew as large as fifty feet long. Others in the genre look at contemporary species like great white and bull sharks, lab-created super genius sharks, sharks in unexpected places like under the sand or in Australian supermarkets, shark-cephalopod hybrids, sharks using storms to migrate and hunt, sharks from beyond the grave and more. It seems just about every possible and a great many more impossible stories of sharks eating people has been told in nature horror, except for the one time that people were regularly, over a long period, eaten by sharks: the Middle Passage.

Most shark species cannot kill people and almost all those that can never think to try as we great apes largely do not register as prey items, not to mention that sharks struggle to hunt outside the water where all people are very nearly all the time. The small number that do sometimes bite people largely do so while being harassed or out of curiosity (a light biting is a ‘what’s this?’ investigatory technique – though this can still be fatal to people). The even smaller number that on rare occasions attack intending to prey often mistake people for more familiar mammals like seals or bite while attempting to procure something attached to a diver as with the catch on a spearfisher’s string. A couple of species are both capable of killing people and also generalist predators that can sometimes register people as potential prey. Only three shark species are confirmed to account for more than ten total human fatalities, the great white, tiger and bull. A fourth, the oceanic whitetip, likely accounts for many fatal attacks in remote, open waters unlikely to be recorded.

Despite the rarity of attacks, sharks occupy a primary location in colonial productions of nature horror – a genre positing a perpetual threat to “man” from an Othered animal or vegetal being, especially animal attack movies. Sharks are imposing beings and larger sharks are capable of tremendous power and rending of flesh in the course of their feeding. And given that people do travel over or swim in waters where sharks live or frequent, let’s call these human-infested waters, the very rare human-as-calories tragedy is inevitable. The potential for horror here is visceral and obvious. Val Plumwood’s essay “On Being Prey” reflects upon her experience surviving a predatory attack by a saltwater crocodile in the north of the Australian settler colony. She describes it as “an experience beyond words of total terror”. The idea of being killed and eaten, or being killed by being eaten, is necessarily horror. This would be the case even if colonialism did not create “a masculinist monster myth” of order being synonymous with human dominance, a “master narrative” of control over and distance from ecological systems, a counterposition of humanity-animality.

Yet for all the horror of the idea of being prey, there is a total lack of malignance in that fate even as many nature horror stories project ideas of diabolical intent upon attacking animals. They were hungry and there you were or, they were wary of your intrusion and you intruded. It’s not a malignant calculus any more than a chameleon has a grudge against a grasshopper. The violence is strictly mis/opportunistic and the individual creatures involved are incidental, just the right combination of lucky/unlucky that defines predator/prey encounters. This is not the case in the Middle Passage. Humans as shark prey in the Middle Passage has purposeful intent from the terroristic to the punitive to the arbitrary. The horror is malignant not by the sharks’ actions, but in how slavers made captive Africans into shark food. Think Jaws combined with Saw combined with Hannibal and you’re in the ballpark, albeit far less horrifying than the actual details which I recommend against investigating for traumatic reasons but also ethical ones around the drive to consume and reproduce anti-black violence.

During the Middle Passage, slavers fed murdered and living Africans to sharks as a convenient disposal of murdered remains and troublesome persons, to terrify surviving captives against escape or suicide overboard, to punish captives involved in insurrections and more. Slavers describe all of that in their contemporary narratives as well as Africans escaping ships to unknown fates including repatriation and liberation as well as death by shark. Slavers murdered at least two million Africans during the Middle Passage and discarded nearly all into the Atlantic. Sharks did not consume all these souls, but they consumed many. If sharks consumed just 1,000 of those dead or living – I found no estimates, reliable or otherwise, but 1,000 is at least a factor of ten below a wildly conservative guess if their frequency in slaver narratives is representative – that would still be nearly 20% higher than all combined fatal and non-fatal shark bites/attacks in the Florida Museum global database hosted by the University of Florida that tracks shark attacks since 1582, and 85% higher than the total verified fatal shark attacks. By any measure, the Middle Passage accounts for the overwhelming preponderance of cases of people being consumed by sharks. The percentage, though unknown in detail, is sufficient to say that it is the the “normal” way sharks eat people with all other examples being statistically peripheral (This if my readings of shark ecology are correct in concluding that most historical ocean-going ships travel too fast for sharks to pursue longer than briefly or are otherwise not attractive to sharks leaving lesser probabilities for shark predation in the event of shipwreck, even incorrectly assuming a historically and geographically flat population density of sharks per square kilometer and oceanic shipwreck distribution).

The Meg, it’s knock-off Megalodon and its pending sequel, 2002’s Shark Attack 3: Megalodon and an earlier Megalodon from the same year, 2012’s Jurassic Shark, 2009’s Mega Shark vs. Giant Octopus or any of the Mega Shark franchise, 2011’s Super Shark and the 2001 Antonio Sabato Jr. vehicle Shark Hunter account for ten of the feature length films about an extinct shark hunting people, a species that never once encountered any great ape in its millions of years of existence. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this. Sci-fi doesn’t have to have much sci in it to be a fun or good story. Over ten impossible megalodon films but not one involving the predominant context of material world consumption of people by sharks. Why are our imaginary universes so rarely grounded in material violences like the Middle Passage? This isn’t just the sci-fi shark attack stories like The Meg, Sharknado and 2-Headed Shark Attack.

I earlier argued that nearly all shark attack films are sci-fi in that sharks are not, as a rule, capable of consuming as much food as they do in shark attack movies. An adult great white shark cannot eat hundreds of pounds of people in two days like in The Shallows, much less in minutes as with Jaws 2. But even in those films portrayed as real-world like Jaws, I’m aware of none that take place in or reference the only historical geography where shark attacks on people were common and predictable. There are films like Frenzy and Open Water with divers and boaters marooned in remote areas in the face of hungry sharks but none of actual marronage from both slavers and their accompanying sharks. This has always been the case in film and tv but not in other mediums.

Petition picture from the University of Virginia website

Scottish abolitionist and radical James Tytler produced in 1792 an early science fiction work in his “The PETITION of the SHARKS of Africa” addressed “To the Right Honourable the Lords Spiritual and Temporal of Great Britain, in Parliament Assembled”. In the petition, sharks collectively beg Parliament to not heed the demands of abolitionists as it will deprive a “numerous body” in “a very flourishing situation” of “many a delicious meal” of “large quantities of their most favourite food” over “the specious plea of humanity” that is abolitionism. Abolitionists made much out of the horror of slavers feeding captive Africans to sharks.

JWM Turner 1840 painting: Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhoon coming on. Picture from Wikipedia

J.W.M. Turner’s 1840 oil on canvas Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On (also called The Slave Ship) horrifically foregrounds a slave ship rollicking in heavy seas with sharks setting upon “the dead and dying” Africans-made-into-commodities thrown overboard. There are other pamphlets, poems, paintings, media accounts and more.

Yet fantastic fiction canon bibliographies do not mention Tytler’s text. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston that displays Turner’s painting describes it as “a striking example of the artist’s fascination with violence both human and elemental” but does not mention the sharks in the painting, no matter that the foreground dominates the canvas. It goes beyond this. The Florida Museum worldwide historical shark attack database linked above does not, as best I can determine, account for a single Middle Passage attack. The Wikipedia pages for “Shark Attack” and the various geographical “List of fatal unprovoked shark attacks” pages do not mention the Middle Passage nor any of the documented African murders and deaths by shark during it. I could not access the entirety of every Discovery Channel Shark Week production but from what I could access or review through secondary sources, the Middle Passage is absent from its documentary coverage as well as that of Blue Planet and other NatGeo, Nature, Nova, BBC and other wildlife documentaries about or featuring sharks. Much like shark attack cinema, every possible and impossible shark attack story can be told except for the ones that comprise the vast preponderance. Why should this be?

Marcus Rediker writes about tall ships in perfect analogy to shark attack cinema in his 2008 article in Atlantic Studies, “History from below the water line: Sharks and the Atlantic slave trade”.

Recently I have been studying one kind of tall ship: the slave ship. During this time I discovered the limit of the romance [with tall ships]. It extends to all tall ships except the most important one. The slave ship is so far from romantic that we cannot bear to look at it, even though it was one of the two main institutions of modern slavery. The other, the plantation, has been studied intensively, but slave ships hardly at all. The rich historical literature has much to say about the origins, time, scale, flows, and profits, but little to say about the vessel that made it possible, even though the slave ship was the mechanism for history’s greatest forced migration, for an entire phase of globalization, an instrument of “commercial revolution” and the making of plantations, empires, capitalism, industrialization. If Europe, Africa, and Americas are haunted by the legacies of race, class, and slavery, the slaver is the ghost ship of our modern consciousness.

Rediker was writing prior to Christina Sharpe’s monumental 2016 volume In the Wake: On Blackness and Being and the research and work it inspires along with some preceding work but his point remains largely true. In Fred Moten’s phrasing, the Middle Passage is “the interpellative event of modernity in general.” It establishes ways of meanings through which we understand the world. The answer to the above questions about investigating every possible and impossible scenario in shark attack movies except for the main one is in Moten’s phrasing. The Middle Passage and African Slavery are frames of reference through which we experience the contemporary world. Settler colonialism destroys native worlds to build the anti-black ones and in this building creates ways of meaning, frames of reference, interpellations, discourses, normativity. As the “interpellative event” the Middle Passage is what creates the world in which shark attack movies are imagined. The narrative gap between the world that creates shark attack movies and the world they purport to portray lies in the difficulty of finding, or thinking to look for, a frame of reference with which to observe our frame of reference.

The 2007 sensationalist documentary Sharks on Trial opens asserting that “sharks terrify us” and “trigger our deepest primeval fears”. “Primeval” in this context is weirdly appropriate in how it suggests the Middle Passage as the “interpellative event of modernity in general,” how it is world building. Some future colonizing empires, geographies or proto-states had earlier descriptions or cultural and linguistic representations of sharks but lost them during the Medieval period. José Castro writes that “Large sharks were known to the Greeks and Romans, and references to large sharks of the Mediterranean are found in the writings of classical writers from Aristotle to Aelian,” but that “Large sharks are conspicuously absent from the medieval bestiaries that described the then known fauna as well as some imaginary animals.” The word shark enters the English and Spanish languages through the Middle Passage. Rediker writes that “the English shark thus seems to have entered the English language through the talk of slave-trade sailors, who may have picked up and adapted the word ‘xoc,’ […] from the Maya in the Caribbean.” Castro notes the “Spanish borrowed the word tiburón from the Carib[s].” Understanding the Middle Passage as modernity’s “interpellative event” means sharks are part of creating the modern world, a synonym for the anti-Black one, making consciousness of them “primeval” indeed.

Works like Thomas Peschak’s 2013 text from University of Chicago Press, Sharks and People: Exploring Our Relationship with the Most Feared Fish in the Sea studiously ignore the medieval pre/proto-European break in shark knowledge instead asserting that “Historians have traced fear of sharks back to ancient times, as far back as the the civilizations of Greece and Rome.” Leaving aside the glaring absence of Kru, Hawai’ian and other non-European coastal and seafaring populations’ shark narratives — including those from the populations from which colonizers took words for sharks — filling in an appropriately blank spot to draw an ahistorical lineage obscures the Middle Passage’s founding role in colonial understandings of the shark as horror fodder. Peschak’s book is geared toward the noble goal of shark conservation while dedicating just one-half of one paragraph amongst 286 pages to the Middle Passage, the only modern period were there was anything close to parity in the numbers of people eaten by sharks and sharks eaten by people. As opposed to today when sharks comprise roughly 99.9999958% of the annual deaths in fatal human-shark encounters and humans around .0000042%, primarily through capitalist enclosure of seascapes and commodification of sealife for rents and profits. Anti-blackness, this formation of a humanity-animality binary with black people positioned as, in Frank Wilderson’s forumulation, commodifiable sites of accumulation and locations for gratuitous violence, provides the grammar for the mass shark slaughters, for making monsters of sharks, that Peschak and others so justly campaign against. Leaving the Middle Passage out of this narrative reduces the legibility of what creates both anti-blackness and mass shark slaughters through capitalist fishing.

Just as shark attack cinema is colonial cultural production, the Middle Passage sharks are a part of a colonial ecology. Their desires were for a mix of shade from the hot tropical sun and the convenient food that often accompanies large, slow moving, floating objects, but slavers deployed those impulses as part of a terror regime. Rediker quotes one source saying

the master of a Guinea-ship, finding a rage for suicide among his slaves, from a notion the unhappy creatures had, that after death they should be restored again to their families, friends, and country; to convince them at least some disgrace should attend them here, he immediately ordered one of their dead bodies to be tied by the heels to a rope, and so let down into the sea; and, though it was drawn up again with great swiftness, yet in that short space, sharks had bit off all but the feet.

Other sources narrate kidnapped Africans being fed alive to sharks for the same purpose of terrorizing others. Sharks then, formed the exterior perimeter of The Hold and were purposefully recruited for that function. Redicker quoting again, “Our way to entice [sharks] was by Towing overboard a dead Negro which they would follow till they had eaten him up.” For colonizers the origins of shark chumming was not to catch sharks but to attract them as predators for the purpose of horror, for the purpose of a living fence.

Christina Sharpe writes, “The belly of the ship births blackness.” The slave ship’s Hold is the indigenous geography of blackness and Black Captivity. The Hold’s geography of Black Captivity intended totalization. If The Hold is where blackness is born, sharks are its birth attendants. One slave ship passenger wrote, per Rediker, “we caught plenty of fish almost every day, especially Sharks, which wee salted, & preserv’d for ye Negroes.” He continued, “They are good victuals, if well dress’d, tho’ some won’t eat them, because they feed upon men; ye Negroes fed very heartily upon them.” Thinking again of Plumwood’s “experience beyond words of total terror” at being crocodile prey, escape overboard from The Hold is exactly this yet compounded with Black Captivity. Death and/or consumption by shark may not offer any freedom from The Hold but could mean being very literally fed back into it or nourishing one’s former captors, mediated by sharks. One’s physical being put to work after biological death is a level of totalitarian control difficult to approach. While the sharks themselves offer no malevolence, they are mediators for slavers’ cruelties, desires and hungers. Almost all shark attack movies aspire towards horror but none approach this, not in topic nor terror. Not even those that make out sharks as illegible monsters, as ‘here be dragons’.

Despite everything written above, I’m neither interested in nor calling for movies or stories about sharks eating captive black people in horror cinema and television. Social media, cinema, TV and carceral systems are already chock full of black death and pain intended for consumption, often under the ruse of “raising awareness”. It’s part of the continual construction and (re)production of anti-blackness. Inside of anti-blackness there is no revolutionary potential in this kind of production of cinematic black death. But grounding our imaginary universes inside material violences does not necessitate reproducing them. Part of cinematic horror, including nature horror, is the relief that comes with the end of the horror affect, as when someone is finally rescued from or kills an attacking shark. In shark attack movies this can mean sharks as secondary terror elements in Middle Passage revolt, survival or escape stories. Or even sharks as intentional allies in vanquishing slavers – an inversion of The Hold as a location of black captivity, instead its wanton destruction becoming what Wilderson describes as “gratuitous freedom” – and so many more possibilities. This second example where the cruel sharks of nature horror can similarly plot in hypothetical Middle Passage stories applies equally to antecedents of other fictional aquatic beings like Ariel from The Little Mermaid and Madison from Splash, Aquaman and Namor in comics and others. Where, in their universes, were their ancestors during the Middle Passage? Like the imaginary villainous sharks of nature horror with their bottomless stomachs, their peoples necessarily encountered the Black Atlantic during the Middle Passage. What happened next?

A shark prop supposed to be a great white reduces the settler population by one. Screencap from Jaws (1975)

Instead of shark attack cinema reproducing anti-black normativity through examining every possible story but the true one, it can offer different reference points for meaning. Instead of anti-blackness being the frame through which the story is told, a different positionality can be the frame that breaks The Hold. A black liberation shark attack story does not the revolution make. But each contribution towards ways of meaning not premised upon anti-blackness creates a new potential hegemony, a new lens through which we engage the world and, in that, a partial end to the present world. It also turns upside down existing shark attack cinema, reframing colonizers being “victimized” by sharks as not horror. Sharks, following “the ghost ship of our modern consciousness” are the heroes haunting the settlers. I don’t want to overstate the potential individual enterprises like what a single shark attack movie against The Hold could do. But it’s hard to imagine action for real change without talking about things. And cinema is one form of conversation. And the nature horror genre can be part of that conversation when it stops giving us every possible story but the true one. Thanks for reading.

Works providing the basis for this essay

Saidiya Hartman Scenes of Subjection

Saidiya Hartman & Frank Wilderson “The Position of the Unthought”

Frank Wilderson Red, White and Black

Fred Moten Stolen Life

Jared Sexton “Unbearable Blackness”

Christina Sharpe In the Wake

Marcus Rediker “History from below the water line: Sharks and the Atlantic slave trade”

Val Plumwood “On Being Prey”